John is sixty years old.

His family once owned a wide stretch of Wyoming land — enough to mean something, enough to feel like inheritance, like promise, like the quiet dignity of roots. But land has a way of shrinking when money runs thin. Generation after generation, they carved off another piece to keep food on the table, until the land was mostly memory and the ranch felt less like a homestead and more like a monument to what used to be.

John never found steady work. He drifted — odd jobs, here and there, the kind of labor that fills days without filling bank accounts. His real community, the one that made him feel seen and heard and righteous, was the bar. And in the bar, there were always other Johns. Men like him, carrying the same grievances, nursing the same wounds, finding the same comfort in the same conclusion: those damn foreigners. Taking the jobs. Ruining the country. Not even bothering to learn the language.

John hated foreigners with the clean, uncomplicated conviction of a man who has been handed his beliefs ready-made, pre-assembled, requiring no thought to maintain. He hated them the way you hate something you’ve always hated, the way you breathe — without noticing, without questioning, without wondering who first put the air there.

His daddy told him. His daddy’s daddy was told the same. And the politicians — generation after generation of them, with their flags and their rallies and their righteous fury — they confirmed it. These outsiders are the reason your life hasn’t worked out. These people, not us. And John believed them, because believing them meant he didn’t have to believe something far more painful: that the system he trusted had never been designed with him in mind.

There is something almost unbearably ironic buried in John’s story, if you’re willing to sit with it. The land his family “owned” — the land they’ve spent a century slowly losing — was itself taken. Taken from people who had lived on it for thousands of years, by ancestors who came from somewhere else, who did not speak the local languages, who imposed their culture by force. John’s family were, in the oldest sense of the word, the foreigners. But history is inconvenient, and politicians are skilled at making people look forward at threats rather than backward at origins.

Here is how it works, and it is not complicated.

When a politician needs to hold power without delivering results, they need a villain. Not a real villain — real villains are complicated, often wealthy, often connected to the very politicians pointing fingers. No, they need a symbolic villain. Someone visible. Someone different. Someone easy to fear.

So, they work the media like an instrument. When a person with a foreign-sounding name commits a crime — any crime, a minor crime, a crime that happens every day in every community — the volume gets turned all the way up. The story runs on a loop. The anchors speak in grave tones. The chyrons are alarming. And for John, sitting in his living room in his dilapidated ranch, the message lands like a revelation: See? This is what they are. This is what they do.

The remote control gets pressed, and John has his evidence. He doesn’t need statistics. He doesn’t need context. He has the image seared into his mind, and the image confirms what he already felt in his gut, what his daddy felt, what the politician standing at the podium has been telling him for years.

And the politician? The politician goes back to work. For the donors. For the corporations. For the quiet machinery of wealth that funds campaigns and expects returns. John, consumed by his hatred, distracted by his fear, is no longer watching what’s actually happening to him. He has been given a gift: someone to blame. And the gift cost the politician nothing.

James Tyrant — let’s call him that, because you know his type — comes from money. His father was in politics too, and wealthy. James became wealthier still, the way certain men always do, not through the dirty labor of the world but through proximity to power, through favors exchanged in rooms John will never enter, through the quiet mechanisms by which policy becomes profit.

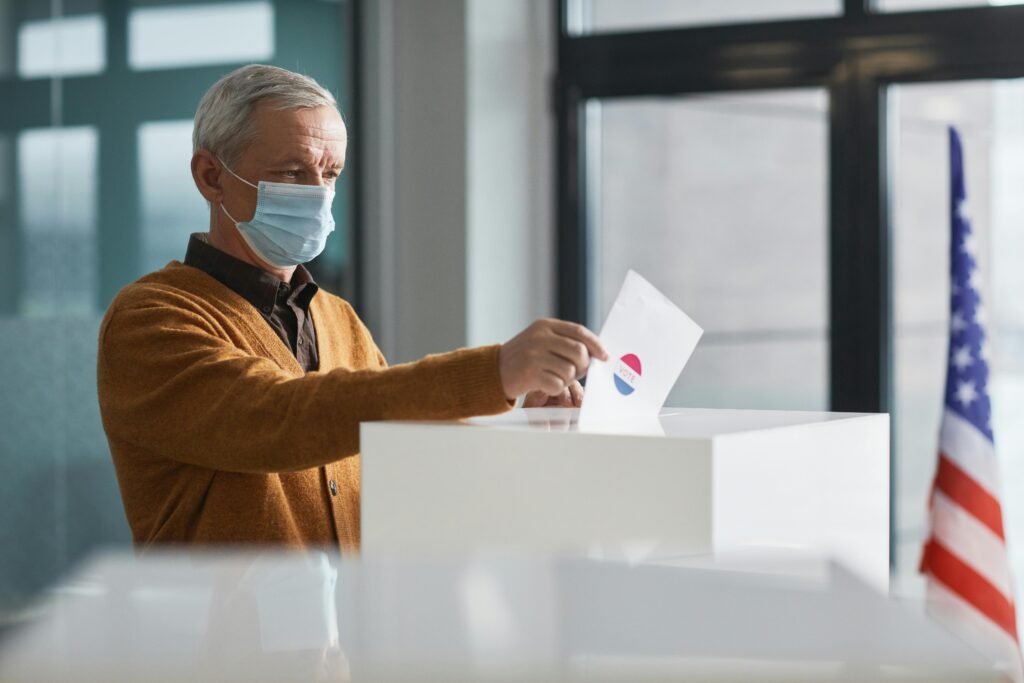

John voted for James Tyrant. John believed in James Tyrant. John stood at rallies and felt something rare: he felt like he mattered. Like someone was finally saying what needed to be said. Like the foreigners would finally be stopped, the border would finally be sealed, and the country would finally return to what it was supposed to be — which in John’s imagination looks something like his grandfather’s Wyoming, green and wide and uncomplicated.

But forty years have passed. The foreigners are still here. More than that — some of them are citizens now. Some of them run businesses, hold degrees, sit in offices. Some of them are doing, quietly and stubbornly, exactly what John’s ancestors once did: building a life in a new place, learning the rules, trying to belong. And John? John is sixty. He is tired. He is sitting in the ranch that keeps shrinking, looking at a life that never opened up the way it was supposed to, and something is shifting in him — a slow, terrible clarity, the kind that only comes when there’s no more road ahead to distract you from where you’ve been.

He thinks about the men who cleaned the roads outside his town. The women who took the housekeeping jobs at the hotels nobody else wanted. The workers bent double in the fields in summer heat, doing the labor that John, as a citizen, considered beneath him. He never thanked them. He never saw them, not really — they were symbols, not people, props in the story he’d been handed.

He thinks about what he spent. Not money. Time. The irreplaceable, non-refundable currency of a human life. Forty years of anger. Forty years of bar-stool grievances and late-night fury at the television. Forty years of hating people he had never truly met, for crimes they had not actually committed against him.

Forty years.

He thinks about all the things he might have done with forty years. Places he never went. People he never became. The dreams he had at twenty — before the hate calcified, before the resentment became identity — vague and bright and full of possibility.

He thinks about James Tyrant, who is richer than ever. Whose children went to the best schools. Who will retire to a second home somewhere warm and write a memoir about his service to the country. Who gave John exactly what John asked for — someone to hate — and in doing so, freed himself to do whatever he wanted.

The foreigners didn’t take John’s life. John gave it away, one year at a time, to a feeling that someone else manufactured for him. The real thieves never crossed a border. They wore suits and stood at podiums and smiled, and they knew — they have always known — that a man consumed by hatred is a man who isn’t paying attention.

This is the tragedy of the Johns of this world, and there are millions of them, in every country, in every era. The mechanism is ancient and reliable: find a group that’s different, make them look frightening, keep the fear fed and fresh, and you will have a loyal following that will never look at you too closely.

It works because it answers something real. John’s life did get harder. The land did disappear. The promises weren’t kept. The pain is genuine, and a man in genuine pain will reach for any explanation that makes the pain make sense. Politicians who traffic in hatred understand this. They are not stupid. They are, in their way, brilliant — brilliant at finding the wound and pressing on it and pointing elsewhere.

The question — the only question that matters — is whether we can feel the hand pressing on the wound and look up in time to see whose hand it is.

John didn’t. Not until the end. Not until sixty, when the years were mostly spent and the hatred had left nothing behind but exhaustion.

But maybe you’re not sixty yet.

Maybe you still have time to ask: who benefits when I’m busy hating this person? Who is getting rich while I’m getting angry? Who is getting free while I’m getting used?

Give a man someone to hate, and you can do anything you want with everything else.

Don’t be John.

Some politicians run on fear because it works. The only thing that makes it stop working is people who refuse to buy it.

Salima

Just me thinking out loud over here